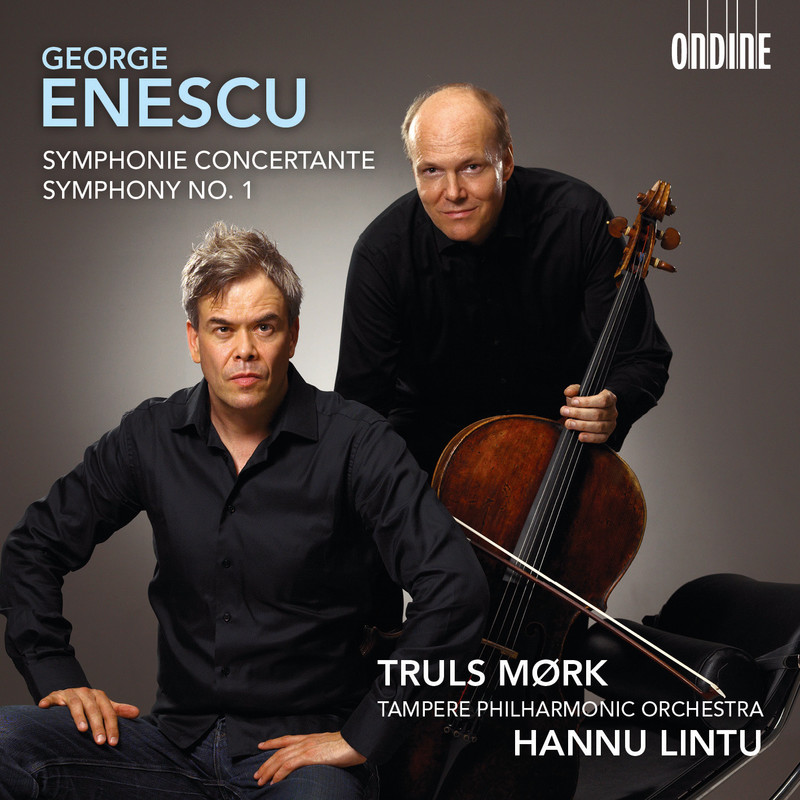

George Enescu: Symphonie Concertante & Symphony No. 1

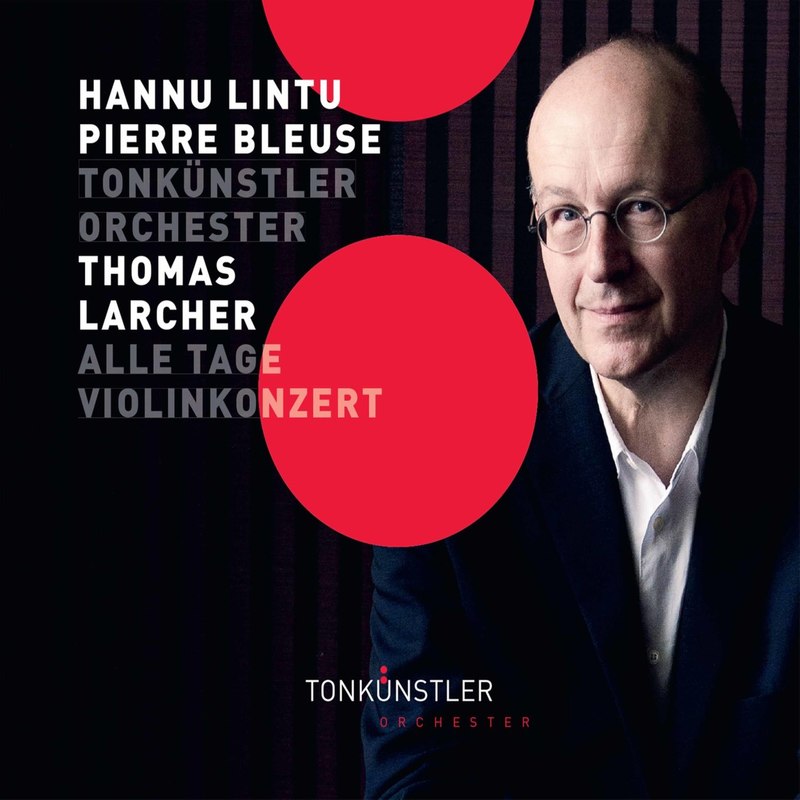

Hannu Lintu

2015-01-10

专辑简介

Hannu Lintu专辑介绍:When George Enescu wrote his Symphonie Concertante in Paris in 1901, he was a young man just reaching his twenties but already a seasoned musician. He had been a dazzling prodigy, entering the Vienna Conservatory at only seven years old and graduating at 13, after which he went on to study at the Paris Conservatory. He had made his performing début as a violinist in Vienna and continued to perform in Paris, where he studied both the violin and composition with Jules Massenet and Gabriel Fauré. A concert of his works was held in Paris in 1897 when he was only 16 years old. His first numbered work, the symphonic suite Poème Roumain (1897), attracted widespread attention, and the two Romanian Rhapsodies (1901, 1902) that he wrote concurrently with the Symphonie Concertante marked his international breakthrough.

Enescu drew on a variety of sources for his broad, flowing late Romantic musical style. Although he became a cosmopolitan at a very yearly age, he never abandoned the national heritage of his native Romania. While studying in Vienna, he immersed himself in the traditions of Germanspeaking central Europe under the strict tutelage of Robert Fuchs, who also gave Sibelius a hard time in his day. At the Paris Conservatory, Enescu was introduced to the French style by Massenet and Fauré. He continued to assimilate new stylistic influences with a remarkable sensitivity, although he never became a Modernist.

Enescu’s talent had not only depth but breadth as well: besides being a composer and a violinist, he also created a career as a pianist, a conductor and a teacher, and his cello playing was not bad either. It was with good reason that his Romanian-French colleague Marcel Mihalovici described him as a ‘complete musician’. The downside of being so multi-talented was that Enescu’s output as a composer in his adult age remained relatively limited, and a number of works remained unfinished for many years because of his other commitments. His magnum opus, the opera Oedipe, took no less than two decades to complete (1910–1931).

Considering how accomplished a musician Enescu was, it is surprising that the Symphonie Concertante in B flat minor for cello and orchestra was the only extensive work featuring a solo instrument that he ever completed. This is particularly remarkable because the cello ranked third among his own instruments, and writing pieces for violin or piano would have allowed him to extend his own performing repertoire. He did write smaller-scale solo pieces for the violin (Ballade, 1895)and the piano (Fantaisie, 1896), and he did plan to write a number of concertante works at various points in his career, but he never finished any of them.

The Symphonie Concertante betrays Enescu’s personal contact with the cello; the soloist is active for most of the duration. He originally intended to give the work the conventional title of Cello Concerto (which still appears as late as on the manuscript of the original solo part) but eventually decided against it. This was apparently not so much because of the role played by the cello but because Enescu wished to emphasise the symphonic gravitas of the work, as opposed to the more insubstantial nature of virtuoso concertos. The work is in the broadly flowing late Romantic style of Enescu’s early career. The Romanian Rhapsodies written around the same time have a clear national flavour, which may also be detected in a more subtle guise in the Symphonie Concertante.

The Symphonie Concertante is in a single movement but has a complex structure. It opens with a section that has an almost processional steady gait. The cello introduces and develops the thematic material for several minutes before the orchestra enters the dialogue. The thematic material grows and develops further until the music goes into a fleeting, scherzo-like section. The slower opening tempo returns in a freely conceived recapitulation leading through a ponderous culmination to a section marked ‘Majestueux’. This launches a determined and positive drive in which the soloist, as in a concerto finale, progresses with brilliance to the final climax.

Enescu wrote his Symphony No. 1, Op. 13 in 1905, and it was premiered in Paris in the following year. It represents the next step in the steady, determined growth of the young composer. Written with a confident hand, it still betrays some of its influences, but these are now better integrated. In fact, it is only in name that this work is the first of its kind, as Enescu had written four unperformed ‘school symphonies’ between 1895 and 1898. In all, he wrote an astonishing amount of music in the 1890s. With healthy self-confidence, Enescu wrote his first official symphony in the heroic key of E flat major, the key of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. Although the work only has three movements, it is music on a grand scale and with grand gestures, where influences from Brahms, Wagner, Richard Strauss and French composers fuse together in a late Romantic sublimation. As in his two subsequent symphonies, Enescu orchestrated the work with broad, full strokes, bringing the music to thundering climaxes; but there is a more sensitive side to it too.

The Symphony opens with a brass unison and then explodes into brilliance and energy. The orchestral texture is rich and varied. The main subject yields through a mysterious transition to the more relaxed second subject. The gradually escalating development leads with a handsome flourish to the recapitulation. The music gains coherence from the rhythmic and motivic similarity of the two principal subjects, and the music progresses flexibly from one section to the next.

The slow movement also begins with a brass sound, though more restrained than the first movement. A horn signal introduces the mysterious mood of the opening section. At times, the half-light and sensuous sound of the music echo the influence of French music. The opening horn signal is continuously present in the texture and finally, after a quieter moment, leads into a more active and emotionally glowing sequence where the movement’s motifs are woven together in beautiful counterpoint. Yet another appearance of the horn signal brings back the mysterious mood of the opening that also concludes the movement.

The finale is shorter and more to the point than the other two movements, as the final movements of symphonies often are. Energetic and determined, it brings the symphony to an uplifting and optimistic close.

Kimmo Korhonen

Translation: Jaakko Mäntyjärvi

专辑曲目

1

George Enescu: Symphony No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 13 - II. Lent

Hannu Lintu

2

George Enescu: Symphonie Concertante for Cello and Orchestra in B flat minor, Op. 8 - I. Assez lent

Hannu Lintu

3

George Enescu: Symphonie Concertante for Cello and Orchestra in B flat minor, Op. 8 - II. Assez lent

Hannu Lintu

4

George Enescu: Symphonie Concertante for Cello and Orchestra in B flat minor, Op. 8 - III. Majestueu

Hannu Lintu

5

George Enescu: Symphony No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 13 - I. Assez vif et rythmé

Hannu Lintu

6